|

[1]

|

Tsiafoulis CG, Trikalitis PN, Prodromidis MI (2005) Synthesis, characterization and performance of vanadium hexacyanoferrate as electrocatalyst of H2O2. Electrochem Commun 7: 1398–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2005.10.001

|

|

[2]

|

Yu Z, Park Y, Chen L, et al. (2015) Preparation of a Superhydrophobic and Peroxidase-like Activity Array Chip for H2O2 Sensing by Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. ACS Appl Mater Inter 7: 23472–23480. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b08643

|

|

[3]

|

Geiszt M, Leto TL (2004) The Nox family of NAD(P)H Oxidases: host defense and beyond. J Biol Chem 279: 51715–51718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400024200

|

|

[4]

|

Giorgio M, Trinei M, Migliaccio E, et al. (2007) Hydrogen peroxide: a metabolic by-product or a common mediator of ageing signals? Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 8: 722–728. doi: 10.1038/nrm2240

|

|

[5]

|

Murphy MP, Holmgren A, Larsson NG, et al. (2011) Unraveling the biological roles of reactive oxygen species. Cell Metab 13: 361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.010

|

|

[6]

|

Niethammer P, Grabher C, Look AT, et al. (2009) A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature 459: 996–999. doi: 10.1038/nature08119

|

|

[7]

|

Rhee SG (2006) H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science 312: 1882–1883. doi: 10.1126/science.1130481

|

|

[8]

|

Huang YY, Chen ACH, Arany P, et al. (2009) Role of reactive oxygen species in low level light therapy. Mechanisms for low-light therapy IV, Proc. SPIE 7165: 716502. doi: 10.1117/12.814890

|

|

[9]

|

Gough DR, Cotter TG (2011) Hydrogen Peroxide: A Jekyll and Hyde Signalling Molecule. Cell Death Dis 2: e213. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.96

|

|

[10]

|

Rojkind M, Dominguez-Rosales JA, Nieto N, et al. (2002) Role of hydrogen peroxide and oxidative stress in healing responses. Cell Mol Life Sci 59: 1872–1891. doi: 10.1007/PL00012511

|

|

[11]

|

Chen W, Cai S, Ren QQ, et al. (2012) Recent advances in electrochemical sensing for hydrogen peroxide: a review. Analyst 137: 49–58. doi: 10.1039/C1AN15738H

|

|

[12]

|

Finkel T, Serrano M, Blasco MA (2007) The common biology of cancer and ageing. Nature 448: 767–774. doi: 10.1038/nature05985

|

|

[13]

|

Finkel T, Holbrook NJ (2000) Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature 408: 239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687

|

|

[14]

|

Pi JB, Bai YS, Zhang Q, et al. (2007) Reactive oxygen species as a signal in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 56: 1783–1791. doi: 10.2337/db06-1601

|

|

[15]

|

Milas NA, Aleksander-Golubovi A (1959) Studies in organic peroxides. XXVI. Organic peroxides derived from acetone and hydrogen peroxide. J Am Chem Soc 81: 6461–6462.

|

|

[16]

|

Swern D, Silbert LS (1963) Studies in the structure of organic peroxides. Anal Chem 35: 880–885. doi: 10.1021/ac60200a034

|

|

[17]

|

McCullough KJ, Morgan AR, Nonhebel DC, et al. (1980) Ketone-Derived peroxides. Part II. Synthetic methods. J Chem Res (S) 34: 629–650.

|

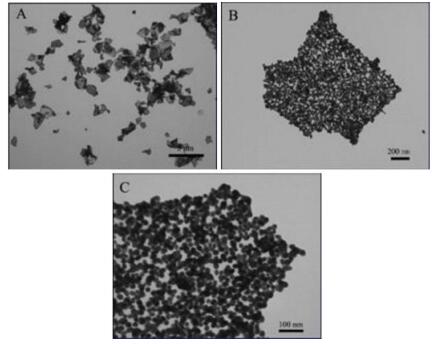

|

[18]

|

Schaefer WP, Fourkas JT, Tiemann BG (1985) Structure of hexamethylene triperoxide diamine. J Am Chem Soc 107: 2461–2463. doi: 10.1021/ja00294a043

|

|

[19]

|

Fourkas JT, Schaefer WP (1986) The structure of a tricyclic peroxide. Acta Crystallogr C 42: 1395–1397. doi: 10.1107/S0108270186092144

|

|

[20]

|

Edward JT, Chubb FL, Gilson DFR, et al. (1999) Cage peroxides having planar bridgehead nitrogen atoms. Can J Chem 77: 1057–1065.

|

|

[21]

|

Jiang D, Peng L, Wen M, et al. (2016) Dopant-assisted positive photoionization ion mobility spectrometry coupled with time-resolved thermal desorption for on-site detection of triacetone triperoxide and hexamethylene trioxide diamine in complex matrices. Anal Chem 88: 4391–4399. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04830

|

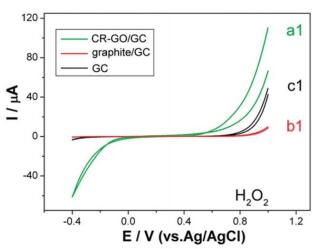

|

[22]

|

Zitrin S, Kraus S, Glattstein B (1983) Identification of Two Rare Explosives. Proccedings of the International Symposium on Analysis and Detection of Explosives.

|

|

[23]

|

Schulte-Ladbeck R, Vogel M, Karst U (2006) Recent methods for the determination of peroxide-based explosives. Anal Bioanal Chem 386: 559–565. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0579-y

|

|

[24]

|

Oxley J, Smith J (2006) Peroxide explosives, In: Schubert H, Kuznetsov A, Detection and disposal of improvised explosives , Netherlands: Springer, 113–121.

|

|

[25]

|

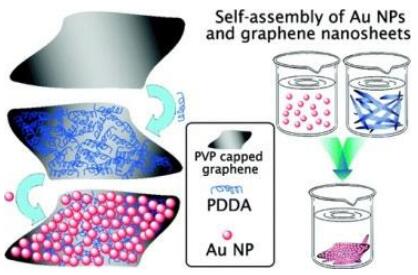

Marshall M, Oxley J (2009) Aspects of Explosives Detection , UK: Elsevier.

|

|

[26]

|

Üzer A, Durmazel S, Erag E, et al. (2017) Determination of hydrogen peroxide and triacetone triperoxide (TATP) with a silver nanoparticles-based turn-on colorimetric sensor. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 247: 98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2017.03.012

|

|

[27]

|

Zhang R, He S, Zhang C, et al. (2015) Three-dimensional Fe- and N-incorporated carbon structures as peroxidase mimics for fluorescence detection of hydrogen peroxide and glucose. J Mater Chem B 3: 4146–4154. doi: 10.1039/C5TB00413F

|

|

[28]

|

Kosman J, Juskowiak B (2011) Peroxidase-mimicking DNAzymes for biosensing applications: A review. Anal Chim Acta 707: 7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2011.08.050

|

|

[29]

|

Deng M, Xu S, Chen F (2014) Enhanced chemiluminescence of the luminol-hydrogen peroxide system by BSA-stabilized Au nanoclusters as a peroxidase mimic and its application. Anal Methods 6: 3117–3123. doi: 10.1039/C3AY42135J

|

|

[30]

|

Liu M, Zhao G, Zhao K, et al. (2009) Direct electrochemistry of hemoglobin at vertically-aligned self-doping TiO2 nanotubes: A mediator-free and biomolecule-substantive electrochemical interface. Electrochem Commun 11: 1397–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2009.05.015

|

|

[31]

|

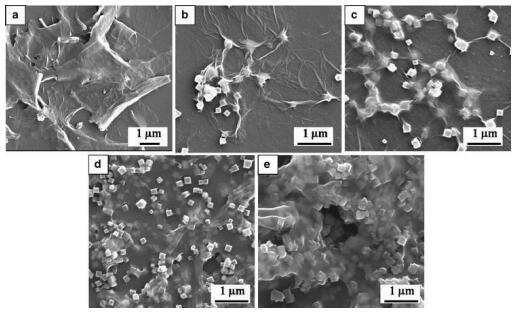

Liu M, Liu R, Chen W (2013) Graphene wrapped Cu2O nanocubes: non-enzymatic electrochemical sensors for the detection of glucose and hydrogen peroxide with enhanced stability. Biosens Bioelectron 45: 206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.02.010

|

|

[32]

|

Ensafi AA, Abarghoui MM, Rezaei B (2014) Electrochemical determination of hydrogen peroxide using copper/porous silicon based non-enzymatic sensor. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 196: 398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.02.028

|

|

[33]

|

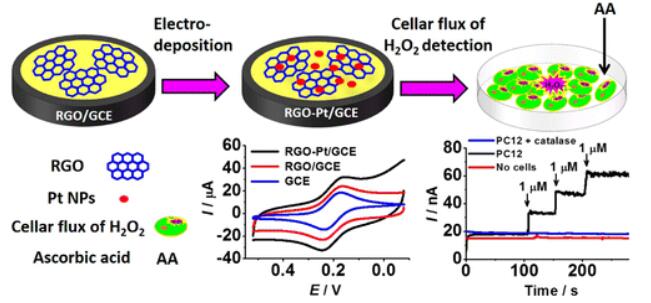

Jana M, Saha S, Khanra P, et al. (2014) Bio-reduction of graphene oxide using drained water from soakedmung beans (Phaseolus aureus L.) and its application as energy storage electrode material. Mater Sci Eng B 186: 33–40.

|

|

[34]

|

Lin D, Su Z, Wei G (2018) Three-dimensional porous reduced graphene oxide decorated with MoS2 quantum dots for electrochemical determination of hydrogen peroxide. Mater Today Chem 7: 76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mtchem.2018.02.001

|

|

[35]

|

Wang L, Wu A, Wei G (2018) Graphene-based aptasensors: from molecule–interface interactions to sensor design and biomedical diagnostics. Analyst 143: 1526–1543. doi: 10.1039/C8AN00081F

|

|

[36]

|

Wang Z, Dai Z (2015) Carbon nanomaterials-based electrochemical biosensors: an overview. Nanoscale 7: 6420–6431. doi: 10.1039/C5NR00585J

|

|

[37]

|

Yang C, Denno ME, Pyakurel P, et al. (2015) Recent trends in carbon nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors for biomolecules: A review. Anal Chim Acta 887: 17–37. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.05.049

|

|

[38]

|

Wang L, Zhang Y, Wu A (2017) Designed graphene-peptide nanocomposites for biosensor applications: A review. Anal Chim Acta 985: 24–40. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2017.06.054

|

|

[39]

|

Kuila T, Bose S, Khanra P, et al. (2011) Recent advances in graphene-based biosensors. Biosens Bioelectron 26: 4637–4648. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2011.05.039

|

|

[40]

|

Zhang R, Chen W (2017) Recent advances in graphene-based nanomaterials for fabricating electrochemical hydrogen peroxide sensors. Biosens Bioelectron 89: 249–268. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.01.080

|

|

[41]

|

Choi W, Lahiri I, Seelaboyina R, et al. (2010) Synthesis of Graphene and its applications: A Review. Crit Rev Solid State 35: 52–71. doi: 10.1080/10408430903505036

|

|

[42]

|

Dreyer RD, Park S, Bielawski C, et al. (2010) The chemistry of graphene oxide. Chem Rev Soc 39: 228. doi: 10.1039/B917103G

|

|

[43]

|

Kim KS, Zhao Y, Jang H, et al. (2009) Large-scale pattern growth of graphene films for stretchable transparent electrodes. Nature 457: 706–710. doi: 10.1038/nature07719

|

|

[44]

|

Kuila T, Bhadra S, Yao D, et al. (2010) Recent advances in graphene based polymer composites. Prog Polym Sci 35: 1350–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2010.07.005

|

|

[45]

|

Park S, Ruoff RS (2009) Chemical methods for the production of graphenes. Nat Nanotechnol 4: 217–224. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.58

|

|

[46]

|

Novoselov KS, Geim AK, Morozov SV, et al. (2004) Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films. Science 306: 666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1102896

|

|

[47]

|

Sharma D, Kanchi S, Sabela MI, et al. (2016) Insight into the biosensing of graphene oxide: Present and future prospects. Arab J Chem 9: 238–261. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.07.015

|

|

[48]

|

Raccichini R, Varzi A, Passerini S, et al. (2015) The role of graphene for electrochemical energy storage. Nat Mater 14: 271–279. doi: 10.1038/nmat4170

|

|

[49]

|

Pei S, Cheng HM (2012) The reduction of graphene oxide. Carbon 50: 3210–3228. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2011.11.010

|

|

[50]

|

Chhetri S, Samanta P, Murmu NC, et al. (2016) Effect of dodecyal amine functionalized graphene on the mechanical and thermal properties of epoxy-based composites. Polym Eng Sci 56: 1221–1228. doi: 10.1002/pen.24355

|

|

[51]

|

He H, Gao C (2010) General Approach to Individually Dispersed, Highly Soluble, and Conductive Graphene Nanosheets Functionalized by Nitrene Chemistry. Chem Mater 22: 5054–5064. doi: 10.1021/cm101634k

|

|

[52]

|

Yu D, Yang Y, Durstock M, et al. (2010) Soluble P3HT-Grafted Graphene for Efficient Bilayer−Heterojunction Photovoltaic Devices. ACS Nano 4: 5633–5640. doi: 10.1021/nn101671t

|

|

[53]

|

Hamilton CE, Lomeda JR, Sun Z, et al. (2009) High-Yield Organic Dispersions of Unfunctionalized Graphene. Nano Lett 9: 3460–3462. doi: 10.1021/nl9016623

|

|

[54]

|

Park JH, Mitchel WC, Smith HE (2010) Studies of interfacial layers between 4H-SiC (0 0 0 1) and graphene. Carbon 48: 1670–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2009.12.006

|

|

[55]

|

Ernst A, Makowski O, Kowalewska B, et al. (2007) Hybrid bioelectrocatalyst for hydrogen peroxide reduction: Immobilization of enzyme within organic–inorganic film of structured Prussian Blue and PEDOT. Bioelectrochemistry 71: 23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2006.12.004

|

|

[56]

|

Zhang W, Li G (2004) Third-generation biosensors based on the direct electron transfer of proteins. Anal Sci 20: 603–609. doi: 10.2116/analsci.20.603

|

|

[57]

|

Zhu X, Yuri I, Gan X, et al. (2007) Electrochemical study of the effect of nano-zinc oxide on microperoxidase and its application to more sensitive hydrogen peroxide biosensor preparation. Biosens Bioelectron 22: 1600–1604. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.07.007

|

|

[58]

|

Zhang R, Chen W (2013) Non-precious Ir–V bimetallic nanoclusters assembled on reduced graphene nanosheets as catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. J Mater Chem A 1: 11457–11464. doi: 10.1039/c3ta12067h

|

|

[59]

|

Zuo X, He S, Li D, et al. (2010) Graphene Oxide-Facilitated Electron Transfer of Metalloproteins at Electrode Surfaces. Langmuir 26: 1936–1939. doi: 10.1021/la902496u

|

|

[60]

|

Mani V, Dinesh B, Chen SM, et al. (2014) Direct electrochemistry of myoglobin at reduced graphene oxide-multiwalled carbon nanotubes-platinum nanoparticles nanocomposite and biosensing towards hydrogen peroxide and nitrite. Biosens Bioelectron 53: 420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.09.075

|

|

[61]

|

Lu Q, Dong X, Li LJ, et al. (2010) Direct electrochemistry-based hydrogen peroxide biosensor formed from single-layer graphene nanoplatelet–enzyme composite film. Talanta 82: 1344–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2010.06.061

|

|

[62]

|

Li Y, Zhang W, Zhang L, et al. (2017) Sequence-designed peptide nanofibers bridged conjugation of graphene quantum dots with graphene oxide for high performance electrochemical hydrogen peroxide biosensor. Adv Mater Interfaces 4: 1600895. doi: 10.1002/admi.201600895

|

|

[63]

|

Xiao Y, Ju HX, Chen HY (1999) Hydrogen peroxide sensor based on horseradish peroxidase-labeled Au colloids immobilized on gold electrode surface by cysteamine monolayer. Anal Chim Acta 391: 73–82. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(99)00196-8

|

|

[64]

|

Zeng Q, Cheng J, Tang L, et al. (2010) Self-Assembled graphene–enzyme hierarchical nanostructures for electrochemical biosensing. Adv Funct Mater 20: 3366–3372. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201000540

|

|

[65]

|

Chang Q, Tang HQ (2014) Optical determination of glucose and hydrogen peroxide using a nanocomposite prepared from glucose oxidase and magnetite nanoparticles immobilized on graphene oxide. Microchim Acta 181: 527–534. doi: 10.1007/s00604-013-1145-x

|

|

[66]

|

Li M, Xu S, Tang M, et al. (2011) Direct electrochemistry of horseradish peroxidase on graphene-modified electrode for electrocatalytic reduction towards H2O2. Electrochim Acta 56: 1144–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2010.10.034

|

|

[67]

|

Vilian ATE, Chen SM (2014) Simple approach for the immobilization of horseradish peroxidase on poly-L-histidine modified reduced graphene oxide for amperometric determination of dopamine and H2O2. RSC Adv 4: 55867–55876. doi: 10.1039/C4RA09011J

|

|

[68]

|

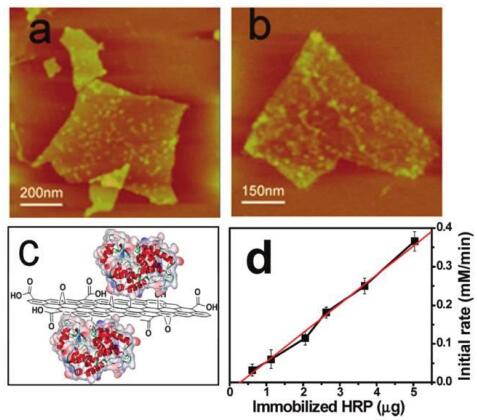

Zhang J, Zhang F, Yang H, et al. (2010) Graphene oxide as a matrix for enzyme immobilization. Langmuir 26: 6083–6085. doi: 10.1021/la904014z

|

|

[69]

|

Fan Z, Lin Q, Gong P, et al. (2015) A new enzymatic immobilization carrier based on graphene capsule for hydrogen peroxide biosensors. Electrochim Acta 151: 186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2014.11.022

|

|

[70]

|

Cui Y, Zhang B, Liu B, et al. (2011) Sensitive detection of hydrogen peroxide in foodstuff using an organic-inorganic hybrid multilayer-functionalized graphene biosensing platform. Microchim Acta 174: 137–144. doi: 10.1007/s00604-011-0608-1

|

|

[71]

|

Sheng Q, Wang M, Zheng J (2011) A novel hydrogen peroxide biosensor based on enzymatically induced deposition of polyaniline on the functionalized graphene–carbon nanotube hybrid materials. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 160: 1070–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2011.09.028

|

|

[72]

|

Wang T, Zhu Y, Li G, et al. (2011) A novel hydrogen peroxide biosensor based on the BPT/AuNPs/graphene/HRP composite. Sci China Chem 54: 1645. doi: 10.1007/s11426-011-4360-5

|

|

[73]

|

Wang T, Liu J, Ren J, et al. (2015) Mimetic biomembrane–AuNPs–graphene hybrid as matrix for enzyme immobilization and bioelectrocatalysis study. Talanta 143: 438–441. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.05.022

|

|

[74]

|

Radhakrishnan S, Kim SJ (2015) An enzymatic biosensor for hydrogen peroxide based on one-pot preparation of CeO2-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite. RSC Adv 5: 12937–12943. doi: 10.1039/C4RA12841A

|

|

[75]

|

Wang S, Zhu Y, Yang X, et al. (2014) Photoelectrochemical detection of H2O2 based on flower-like CuIuS2-graphene hybrid. Electroanalysis 26: 573–580. doi: 10.1002/elan.201300515

|

|

[76]

|

Zhang C, Yang X, Wu F, et al. (2012) Study on a disposable hydrogen peroxide biosensor based on Au-graphene-HRP-Nafion biocomposites modified screen-printed carbon electrodes. Sci Technol Food Ind 33: 317–321.

|

|

[77]

|

Song H, Ni Y, Kokot S (2014) Investigations of an electrochemical platform based on the layered MoS2–graphene and horseradish peroxidase nanocomposite for direct electrochemistry and electrocatalysis. Biosens Bioelectron 56: 137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.01.014

|

|

[78]

|

Deng K, Zhou J, Li X (2013) Noncovalent nanohybrid of ferrocene with chemically reduced graphene oxide and its application to dual biosensor for hydrogen peroxide and choline. Electrochim Acta 95: 18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2013.02.009

|

|

[79]

|

Zhou K, Zhu Y, Yang X, et al. (2010) A novel hydrogen peroxide biosensor based on Au–graphene–HRP–chitosan biocomposites. Electrochim Acta 55: 3055–3060. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2010.01.035

|

|

[80]

|

Lv X, Weng J (2013) Ternary Composite of hemin, gold nanoparticles and graphene for highly efficient decomposition of hydrogen peroxide. Sci Rep 3: 3285–3294. doi: 10.1038/srep03285

|

|

[81]

|

Wang S, Ahu Y, Yang X, et al. (2014) Photoelectrochemical detection of H2O2 based on flower like CuInS2-graphene hybrid. Electroanalysis 26: 573–580. doi: 10.1002/elan.201300515

|

|

[82]

|

Radhakrishnan S, Kim SJ (2015) An enzymatic biosensor for hydrogen peroxide based on one-pot preparation of CeO2-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite. RSC Adv 5: 12937–12943. doi: 10.1039/C4RA12841A

|

|

[83]

|

Nandini S, Nalini S, Manjunatha R, et al. (2013) Electrochemical biosensor for the selective determination of hydrogen peroxide based on the co-deposition of palladium, horseradish peroxidase on functionalized-graphene modified graphite electrode as composite. J Electroanal Chem 689: 233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2012.11.004

|

|

[84]

|

Nalini S, Nandini S, Shanmurugan S, et al. (2014) Amperometric hydrogen peroxide and cholesterol biosensors designed by using hierarchical curtailed silver flowers functionalized graphene and enzymes deposits. J Solid State Electr 18: 685–701. doi: 10.1007/s10008-013-2305-y

|

|

[85]

|

Liu H, Su X, Duan C, et al. (2014) Microwave-assisted hydrothermal synthesis of Au NPs–Graphene composites for H2O2 detection. J Electroanal Chem 731: 36–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2014.08.013

|

|

[86]

|

Cheng Y, Feng B, Yang X, et al. (2013) Electrochemical biosensing platform based on carboxymethyl cellulose functionalized reduced graphene oxide and hemoglobin hybrid nanocomposite film. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 182: 288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2013.03.007

|

|

[87]

|

Wang Y, Zhang H, Yao D, et al. (2013) Direct electrochemistry of hemoglobin on graphene/Fe2O3 nanocomposite-modified glass carbon electrode and its sensitive detection for hydrogen peroxide. J Solid State Electr 17: 881–887. doi: 10.1007/s10008-012-1939-5

|

|

[88]

|

Wang C, Zou X, Wang Q, et al. (2014) A nitrite and hydrogen peroxide sensor based on Hb adsorbed on Au nanorods and graphene oxide coated by polydopamine. Anal Methods 6: 758–765. doi: 10.1039/C3AY41550C

|

|

[89]

|

Zhang L, Han G, Liu Y, et al. (2014) Immobilizing haemoglobin on gold/graphene–chitosan nanocomposite as efficient hydrogen peroxide biosensor. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 197: 164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.02.077

|

|

[90]

|

He Y, Zheng J, Li K, et al. (2010) A hydrogen peroxide biosensor based on room temperature ionic liquid functionalized graphene modified carbon ceramic electrode. Chinese J Chem 28: 2507–2512. doi: 10.1002/cjoc.201190030

|

|

[91]

|

Xie L, Xu Y, Cao X (2013) Hydrogen peroxide biosensor based on hemoglobin immobilized at graphene, flower-like zinc oxide, and gold nanoparticles nanocomposite modified glassy carbon electrode. Colloid Surface B 107: 245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.02.020

|

|

[92]

|

Zhou Y, Yin H, Meng X, et al. (2012) Direct electrochemistry of sarcosine oxidase on graphene, chitosan and silver nanoparticles modified glassy carbon electrode and its biosensing for hydrogen peroxide. Electrochim Acta 71: 294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.04.014

|

|

[93]

|

Huang KJ, Niu DJ, Liu X, et al. (2011) Direct electrochemistry of catalase at amine-functionalized graphene/gold nanoparticles composite film for hydrogen peroxide sensor. Electrochim Acta 56: 2947–2953. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2010.12.094

|

|

[94]

|

Zhang B, Cui Y, Chen H, et al. (2011) A new electrochemical biosensor for determination of hydrogen peroxide in food based on well-dispersive gold nanoparticles on graphene oxide. Electroanalysis 23: 1821–1829. doi: 10.1002/elan.201100171

|

|

[95]

|

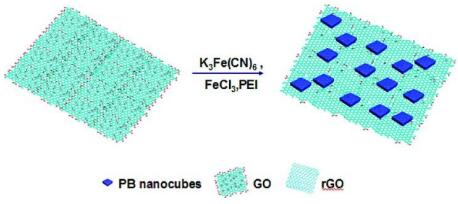

Cao L, Liu Y, Zhang B, et al. (2010) In situ controllable growth of Prussian blue nanocubes on reduced graphene oxide: facile synthesis and their application as enhanced nanoelectrocatalyst for H2O2 reduction. ACS Appl Mater Inter 2: 2339–2346. doi: 10.1021/am100372m

|

|

[96]

|

Qian L, Zheng R, Zheng L (2013) Fabrication of Prussian blue nanocubes through reducing a single-source precursor with graphene oxide and their electrocatalytic activity for H2O2. J Nanopart Res 15: 1806. doi: 10.1007/s11051-013-1806-z

|

|

[97]

|

Yang JH, Myoung N, Hong HG (2012) Facile and controllable synthesis of Prussian blue on chitosan-functionalized graphene nanosheets for the electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide. Electrochim Acta 81: 37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.07.038

|

|

[98]

|

Liang G, Zheng L, Bao S, et al. (2015) Graphene-induced tiny flowers of organometallic polymers with ultrathin petals for hydrogen peroxide sensing. Carbon 93: 719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2015.06.005

|

|

[99]

|

Zhang Y, Xie J, Xiao S, et al. (2014) Facile and controllable synthesis of Prussian blue nanocubes on TiO2–graphene composite nanosheets for nonenzymatic detection of hydrogen peroxide. Anal Methods 6: 9761–9768. doi: 10.1039/C4AY02418D

|

|

[100]

|

Li SJ, Du JM, Shi YF, et al. (2012) Functionalization of graphene with Prussian blue and its application for amperometric sensing of H2O2. J Solid State Electr 16: 2235–2241. doi: 10.1007/s10008-012-1653-3

|

|

[101]

|

Gong H, Sun M, Fan R, et al. (2013) One-step preparation of a composite consisting of graphene oxide, Prussian blue and chitosan for electrochemical sensing of hydrogen peroxide. Microchim Acta 180: 295. doi: 10.1007/s00604-012-0929-8

|

|

[102]

|

Wang L, Ye Y, Lu X, et al. (2013) Prussian blue nanocubes on nitrobenzene-functionalized reduced graphene oxide and its application for H2O2 biosensing. Electrochim Acta 114: 223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2013.10.073

|

|

[103]

|

Liang G, Zheng L, Bao S, et al. (2015) Graphene-induced tiny flowers of organometallic polymers with ultrathin petals for hydrogen peroxide sensing. Carbon 93: 719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2015.06.005

|

|

[104]

|

Niu X, Li X, Pan J, et al. (2016) Recent advances in non-enzymatic electrochemical glucose sensors based on nonprecious transition metal materials: opportunities and challenges. RSC Adv 6: 84893–84905. doi: 10.1039/C6RA12506A

|

|

[105]

|

Zhou M, Zhai Y, Dong S (2009) Electrochemical sensing and biosensing platform based on chemically reduced graphene oxide. Anal Chem 81: 5603–5613. doi: 10.1021/ac900136z

|

|

[106]

|

Banks CE, Moore RR, Davies TJ, et al. (2004) Investigation of modified basal plane pyrolytic graphite electrodes: definitive evidence for the electrocatalytic properties of the ends of carbon nanotubes. Chem Commun 16: 1804–1805.

|

|

[107]

|

Banks CE, Davies TJ, Wildgoose GG, et al. (2005) Electrocatalysis at graphite and carbon nanotube modified electrodes: edge-plane sites and tube ends are the reactive sites. Chem Commun 7: 829–841.

|

|

[108]

|

Banks CE, Compton RG (2005) Exploring the electrocatalytic sites of carbon nanotubes for NADH detection: an edge plane pyrolytic graphite electrode study. Analyst 130: 1232–1239. doi: 10.1039/b508702c

|

|

[109]

|

Takahashi S, Abiko N, Anzai JI (2013) Redox Response of Reduced Graphene Oxide-Modified Glassy Carbon Electrodes to Hydrogen Peroxide and Hydrazine. Materials 6: 1840–1850. doi: 10.3390/ma6051840

|

|

[110]

|

Hamilton CE, Lomeda JR, Sun Z, et al. (2009) High-yield organic dispersions of unfunctionalized graphene. Nano Lett 9: 3460–3062. doi: 10.1021/nl9016623

|

|

[111]

|

Liang Y, Wu D, Feng X, et al. (2009) Dispersion of graphene sheets in organic solvent supported by ionic interactions. Adv Mater 21: 1679–1683. doi: 10.1002/adma.200803160

|

|

[112]

|

Lv W, Guo M, Liang MH, et al. (2010) Graphene-DNA hybrids: self-assembly and electrochemical detection performance. J Mater Chem 20: 6668–6673. doi: 10.1039/c0jm01066a

|

|

[113]

|

Woo S, Kim YR, Chung TK, et al. (2012) Synthesis of a graphene–carbon nanotube composite and its electrochemical sensing of hydrogen peroxide. Electrochim Acta 59: 509–514. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2011.11.012

|

|

[114]

|

Nayak P, Santhosh PN, Ramaprabhu S (2014) Synthesis of Au-MWCNT–Graphene hybrid composite for the rapid detection of H2O2 and glucose. RSC Adv 4: 41670–41677. doi: 10.1039/C4RA05353B

|

|

[115]

|

Gu H, Yang Y, Tian J, et al. (2013) Photochemical synthesis of noble metal (Ag, Pd, Au, Pt) on Graphene/ZnO multihybrid nanoarchitectures as electrocatalysis for H2O2 reduction. ACS Appl Mater Inter 5: 6762–6768. doi: 10.1021/am401738k

|

|

[116]

|

Yuan B, Xu C, Liu L, et al. (2014) Polyethylenimine-bridged graphene oxide–gold film on glassy carbon electrode and its electrocatalytic activity toward nitrite and hydrogen peroxide. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 198: 55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.03.014

|

|

[117]

|

Chang H, Wang X, Shiu KK, et al. (2013) Layer-by-layer assembly of graphene, Au and poly(toluidine blue O) films sensor for evaluation of oxidative stress of tumor cells elicited by hydrogen peroxide. Biosens Bioelectron 41: 789–794. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2012.10.001

|

|

[118]

|

Li SJ, Shi YF, Liu L, et al. (2012) Electrostatic self-assembly for preparation of sulfonated graphene/gold nanoparticle hybrids and their application for hydrogen peroxide sensing. Electrochim Acta 85: 628–635. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.08.118

|

|

[119]

|

Liu R, Li S, Zhang G, et al. (2014) Polyoxometalate-Mediated Green Synthesis of Graphene and Metal Nanohybrids: High-Performance Electrocatalysts. J Clust Sci 25: 711–740. doi: 10.1007/s10876-013-0644-6

|

|

[120]

|

Zhang P, Huang Y, Lu X, et al. (2014) One-Step Synthesis of Large-Scale Graphene Film Doped with Gold Nanoparticles at Liquid–Air Interface for Electrochemistry and Raman Detection Applications. Langmuir 30: 8980–8989. doi: 10.1021/la5024086

|

|

[121]

|

Zhang P, Zhang X, Zhang S, et al. (2013) One-pot green synthesis, characterizations, and biosensor application of self-assembled reduced graphene oxide–gold nanoparticle hybrid membranes. J Mater Chem B 1: 6525–6531. doi: 10.1039/c3tb21270j

|

|

[122]

|

Zhang Y, Liu Y, He J, et al. (2013) Electrochemical behavior of graphene/Nafion/Azure I/Au nanoparticles composites modified glass carbon electrode and its application as nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor. Electrochim Acta 90: 550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.12.068

|

|

[123]

|

Fang Y, Guo S, Zhu C, et al. (2010) Self-Assembly of cationic polyelectrolyte-functionalized graphene nanosheets and gold nanoparticles: a two-dimensional heterostructure for hydrogen peroxide sensing. Langmuir 26: 11277–11282. doi: 10.1021/la100575g

|

|

[124]

|

Xi Q, Chen X, Evans DG, et al. (2012) Gold nanoparticle-embedded porous graphene thin films fabricated via layer-by-layer self-assembly and subsequent thermal annealing for electrochemical sensing. Langmuir 28: 9885–9892. doi: 10.1021/la301440k

|

|

[125]

|

Bai X, Shiu KK (2014) Investigation of the optimal weight contents of reduced graphene oxide–gold nanoparticles composites and theirs application in electrochemical biosensors. J Electroanal Chem 720: 84–91.

|

|

[126]

|

Pang P, Yang Z, Xiao S, et al. (2014) Nonenzymatic amperometric determination of hydrogen peroxide by graphene and gold nanorods nanocomposite modified electrode. J Electroanal Chem 727: 27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2014.05.028

|

|

[127]

|

Hu J, Li F, Wang K, et al. (2012) One-step synthesis of graphene–AuNPs by HMTA and the electrocatalytical application for O2 and H2O2. Talanta 93: 345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2012.02.050

|

|

[128]

|

Maji SK, Sreejith S, Mandal AK, et al. (2014) Immobilizing gold nanoparticles in mesoporous silica covered reduced graphene oxide: a hybrid material for cancer cell detection through hydrogen peroxide sensing. ACS Appl Mater Inter 6: 13648–13656. doi: 10.1021/am503110s

|

|

[129]

|

Ju J, Chen W (2015) In situ growth of surfactant-free gold nanoparticles on nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots for electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide in biological environments. Anal Chem 87: 1903–1910. doi: 10.1021/ac5041555

|

|

[130]

|

Fan Y, Yang X, Yang C, et al. (2012) Au-TiO2/Graphene nanocomposite film for electrochemical sensing of hydrogen peroxide and NADH. Electroanalysis 24: 1334–1339. doi: 10.1002/elan.201200008

|

|

[131]

|

Kumar GG, Babu KJ, Nahm KS, et al. (2014) A facile one-pot green synthesis of reduced graphene oxide and its composites for non-enzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor applications. RSC Adv 4: 7944–7951. doi: 10.1039/c3ra45596c

|

|

[132]

|

Zhang C, Zhang Y, Miao Z, et al. (2016) Dual-function amperometric sensors based on poly(diallydimethylammoniun chloride)-functionalized reduced graphene oxide/manganese dioxide/gold nanoparticles nanocomposite. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 222: 663–231. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2015.08.114

|

|

[133]

|

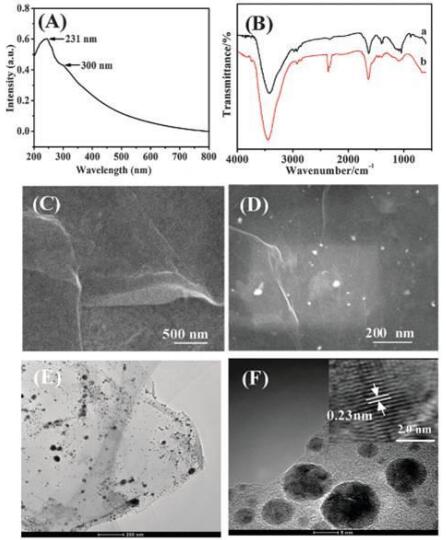

Li XR, Xu MC, Chen HY, et al. (2015) Bimetallic Au@Pt@Au core–shell nanoparticles on graphene oxide nanosheets for high-performance H2O2 bi-directional sensing. J Mater Chem B 3: 4355–4362. doi: 10.1039/C5TB00312A

|

|

[134]

|

Shang L, Zeng B, Zhao F (2015) Fabrication of novel nitrogen-doped graphene–hollow AuPd nanoparticle hybrid films for the highly efficient electrocatalytic reduction of H2O2. ACS Appl Mater Inter 7: 122–128. doi: 10.1021/am507149y

|

|

[135]

|

Wang X, Guo X, Chen J, et al. (2017) Au nanoparticles decorated graphene/nickel foam nanocomposite for sensitive detection of hydrogen peroxide. J Mater Sci Technol 33: 246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jmst.2016.11.029

|

|

[136]

|

Liu Y, Guo X, Zhao L, et al. (2018) Facile preparation of surfactant-free Au NPs/RGO/Ni foam for degradation of 4-nitrophenol and detection of hydrogen peroxide. Nanotechnology 29: 235706. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aab936

|

|

[137]

|

Liu Y, Guo X, Zhu L, et al. (2017) ZnO nanosheets-assisted immobilization of Ag nanoparticles on graphene/Ni foam for highly efficient reduction of 4-nitrophenol. RSC Adv 7: 16924–16930. doi: 10.1039/C7RA01296A

|

|

[138]

|

Fu L, Lai G, Jia B, et al. (2015) Preparation and electrocatalytic properties of polydopamine functionalized reduced graphene oxide-silver nanocomposites. Electrocatalysis 6: 72–76. doi: 10.1007/s12678-014-0219-9

|

|

[139]

|

Liu S, Tian J, Wang L, et al. (2011) Microwave-assisted rapid synthesis of Ag nanoparticles/graphene nanosheet composites and their application for hydrogen peroxide detection. J Nanopart Res 13: 4539–4548. doi: 10.1007/s11051-011-0410-3

|

|

[140]

|

Tian Y, Liu Y, Wang W, et al. (2015) Sulfur-doped graphene-supported Ag nanoparticles for nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide detection. J Nanopart Res 4: 193.

|

|

[141]

|

Zhang M, Wang Z (2013) Nanostructured silver nanowires-graphene hybrids for enhanced electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide. Appl Phys Lett 102: 213104–213108. doi: 10.1063/1.4807921

|

|

[142]

|

Yu B, Feng J, Liu S, et al. (2013) Preparation of reduced graphene oxide decorated with high density Ag nanorods for non-enzymatic hydrogen peroxide detection. RSC Adv 3: 14303–14307. doi: 10.1039/c3ra41755g

|

|

[143]

|

Liu S, Tian J, Wang L, et al. (2010) Stable aqueous dispersion of graphene nanosheets: noncovalent functionalization by a polymeric reducing agent and their subsequent decoration with Ag nanoparticles for enzymeless hydrogen peroxide detection. Macromolecules 43: 10078–10083. doi: 10.1021/ma102230m

|

|

[144]

|

Liu S, Wang L, Tian J, et al. (2011) Aniline as a dispersing and stabilizing agent for reduced graphene oxide and its subsequent decoration with Ag nanoparticles for enzymeless hydrogen peroxide detection. J Colloid Interf Sci 363: 615–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.07.083

|

|

[145]

|

Yang Z, Qi C, Zheng X, et al. (2015) Facile synthesis of silver nanoparticle-decorated graphene oxide nanocomposites and their application for electrochemical sensing. New J Chem 39: 9358–9362. doi: 10.1039/C5NJ01621E

|

|

[146]

|

Wang W, Xie Y, Xia C, et al. (2014) Titanium dioxide nanotube arrays modified with a nanocomposite of silver nanoparticles and reduced graphene oxide for electrochemical sensing. Microchim Acta 181: 1325–1331. doi: 10.1007/s00604-014-1258-x

|

|

[147]

|

Nia PM, Lorestani F, Meng WP, et al. (2015) A novel non-enzymatic H2O2 sensor based on polypyrrole nanofibers–silver nanoparticles decorated reduced graphene oxide nano composites. Appl Surf Sci 332: 648–656. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.01.189

|

|

[148]

|

Sawangphruk M, Sanguansak Y, Krittayavathananon A, et al. (2014) Silver nanodendrite modified graphene rotating disk electrode for nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide detection. Carbon 70: 287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2014.01.010

|

|

[149]

|

Wang L, Zhu H, Hou H, et al. (2012) A novel hydrogen peroxide sensor based on Ag nanoparticles electrodeposited on chitosan-graphene oxide/cysteamine-modified gold electrode. J Solid State Electr 16: 1693–1700. doi: 10.1007/s10008-011-1576-4

|

|

[150]

|

Wang Q, Yun Y (2013) Nonenzymatic sensor for hydrogen peroxide based on the electrodeposition of silver nanoparticles on poly(ionic liquid)-stabilized graphene sheets. Microchim Acta 180: 261–268. doi: 10.1007/s00604-012-0921-3

|

|

[151]

|

Zhu J, Kim KS, Liu Z, et al. (2014) Electroless Deposition of silver nanoparticles on graphene oxide surface and its applications for the detection of hydrogen peroxide. Electroanalysis 26: 2513–2519. doi: 10.1002/elan.201400384

|

|

[152]

|

Bai W, Nie F, Zheng J, et al. (2014) Novel Silver Nanoparticle–Manganese Oxyhydroxide–Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite Prepared by Modified Silver Mirror Reaction and Its Application for Electrochemical Sensing. ACS Appl Mater Inter 6: 5439–5449. doi: 10.1021/am500641d

|

|

[153]

|

Lorestani F, Shahnavaz Z, Mn P, et al. (2015) One-step hydrothermal green synthesis of silver nanoparticle-carbon nanotube reduced-graphene oxide composite and its application as hydrogen peroxide sensor. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 208: 389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.11.074

|

|

[154]

|

Yang YQ, Xie HL, Tang J, et al. (2015) Design and preparation of a non-enzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor based on a novel rigid chain liquid crystalline polymer/reduced graphene oxide composite. RSC Adv 5: 63662–63668. doi: 10.1039/C5RA10540D

|

|

[155]

|

Li X, Liu X, Wang W, et al. (2014) High loading Pt nanoparticles on functionalization of carbon nanotubes for fabricating nonenzyme hydrogen peroxide sensor. Biosens Bioelectron 59: 221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.03.046

|

|

[156]

|

You JM, Kim D, Jeon S (2012) Electrocatalytic reduction of H2O2 by Pt nanoparticles covalently bonded to thiolated carbon nanostructures. Electrochim Acta 65: 288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.01.070

|

|

[157]

|

Vanegas DC, Taguchi M, Chaturvedi P, et al. (2014) A comparative study of carbon–platinum hybrid nanostructure architecture for amperometric biosensing. Analyst 139: 660–667. doi: 10.1039/C3AN01718D

|

|

[158]

|

Leonardi SG, Aloisio D, Donato N, et al. (2014) Amperometric Sensing of H2O2 using Pt–TiO2/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites. ChemElectroChem 1: 617–624. doi: 10.1002/celc.201300106

|

|

[159]

|

Liu W, Li C, Zhang P, et al. (2015) Hierarchical polystyrene@reduced graphene oxide–Pt core–shell microspheres for non-enzymatic detection of hydrogen peroxide. RSC Adv 5: 73993–74002. doi: 10.1039/C5RA11532A

|

|

[160]

|

Zhang F, Wang Z, Zhang Y, et al. (2012) Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Pt/Graphene Nanocomposites for Nonenzymatic Hydrogen Peroxide Sensor. Int J Electrochem Sci 7: 1968–1977.

|

|

[161]

|

Gerbec JA, Magana D, Washington A, et al. (2005) Microwave-enhanced reaction rates for nanoparticle synthesis. J Am Chem Soc 127: 15791–15800. doi: 10.1021/ja052463g

|

|

[162]

|

Tu W, Lin H (2000) Continuous Synthesis of Colloidal Metal Nanoclusters by Microwave Irradiation. Chem Mater 12: 564–567. doi: 10.1021/cm990637l

|

|

[163]

|

Liu J, Bo X, Zhao Z, et al. (2015) Highly exposed Pt nanoparticles supported on porous graphene for electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide in living cells. Biosens Bioelectron 74: 71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.06.042

|

|

[164]

|

Bragaru A, Vasile E, Obreja C, et al. (2014) Pt nanoparticles on graphene–polyelectrolyte nanocomposite: Investigation of H2O2 and methanol electrocatalysis. Mater Chem Phys 146: 538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2014.04.012

|

|

[165]

|

Guo S, Wen D, Zhai Y, et al. (2010) Platinum Nanoparticle Ensemble-on-Graphene Hybrid Nanosheet: One-Pot, Rapid Synthesis, and Used as New Electrode Material for Electrochemical Sensing. ACS Nano 4: 3959–3968. doi: 10.1021/nn100852h

|

|

[166]

|

Lu D, Zhang Y, Lin S, et al. (2013) Synthesis of PtAu bimetallic nanoparticles on graphene–carbon nanotube hybrid nanomaterials for nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor. Talanta 112: 111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.03.010

|

|

[167]

|

Liu P, Li J, Liu X, et al. (2015) One-pot synthesis of highly dispersed PtAu nanoparticles–CTAB–graphene nanocomposites for nonenzyme hydrogen peroxide sensor. J Electroanal Chem 751: 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2015.05.027

|

|

[168]

|

Cui X, Wu S, Li Y, et al. (2015) Sensing hydrogen peroxide using a glassy carbon electrode modified with in-situ electrodeposited platinum-gold bimetallic nanoclusters on a graphene surface. Microchim Acta 182: 265–272. doi: 10.1007/s00604-014-1321-7

|

|

[169]

|

Zhang Y, Bai X, Wang X, et al. (2014) Highly sensitive graphene–Pt nanocomposites amperometric biosensor and its application in living cell H2O2 Detection. Anal Chem 86: 9459–9465. doi: 10.1021/ac5009699

|

|

[170]

|

Sun Y, He K, Zhang Z, et al. (2015) Real-time electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide secretion in live cells by Pt nanoparticles decorated graphene–carbon nanotube hybrid paper electrode. Biosens Bioelectron 68: 358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.01.017

|

|

[171]

|

Xu F, Sun Y, Zhang Y, et al. (2011) Graphene–Pt nanocomposite for nonenzymatic detection of hydrogen peroxide with enhanced sensitivity. Electrochem Commun 13: 1131–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2011.07.017

|

|

[172]

|

Xu C, Zhang L, Liu L, et al. (2014) A novel enzyme-free hydrogen peroxide sensor based on polyethylenimine-grafted graphene oxide-Pd particles modified electrode. J Electroanal Chem 731: 67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2014.08.003

|

|

[173]

|

Liu H, Chen X, Huang L, et al. (2014) Palladium Nanoparticles Embedded into Graphene Nanosheets: Preparation, Characterization, and Nonenzymatic Electrochemical Detection of H2O2. Electroanalysis 26: 556–564. doi: 10.1002/elan.201300428

|

|

[174]

|

Chen XM, Cai ZX, Huang ZY, et al. (2013) Ultrafine palladium nanoparticles grown on graphene nanosheets for enhanced electrochemical sensing of hydrogen peroxide. Electrochim Acta 97: 398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2013.02.047

|

|

[175]

|

You JM, Kim D, Kim SK, et al. (2013) Novel determination of hydrogen peroxide by electrochemically reduced graphene oxide grafted with aminothiophenol–Pd nanoparticles. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 178: 450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2013.01.006

|

|

[176]

|

Chen S, Yuan R, Chai Y, et al. (2013) Electrochemical sensing of hydrogen peroxide using metal nanoparticles: a review. Microchim Acta 180: 15–32. doi: 10.1007/s00604-012-0904-4

|

|

[177]

|

Huang Y, Li SFY (2013) Electrocatalytic performance of silica nanoparticles on graphene oxide sheets for hydrogen peroxide sensing. J Electroanal Chem 690: 8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2012.11.041

|

|

[178]

|

Kong FY, Li WW, Wang JY, et al. (2015) Direct electrolytic exfoliation of graphite with hemin and single-walled carbon nanotube: Creating functional hybrid nanomaterial for hydrogen peroxide detection. Anal Chim Acta 884: 37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.05.016

|

|

[179]

|

Lei W, Wu L, Huang W, et al. (2014) Microwave-assisted synthesis of hemin–graphene/poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) nanocomposite for a biomimetic hydrogen peroxide biosensor. J Mater Chem B 2: 4324–4330.

|

|

[180]

|

Palanisamy S, Chen SM, Sarawathi R (2012) A novel nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor based on reduced graphene oxide/ZnO composite modified electrode. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 166: 372–377.

|

|

[181]

|

Kong L, Ren Z, Zheng N, et al. (2015) Interconnected 1D Co3O4 nanowires on reduced graphene oxide for enzymeless H2O2 detection. Nano Res 8: 469–480. doi: 10.1007/s12274-014-0617-6

|

|

[182]

|

Li SJ, Du JM, Zhang JP, et al. (2014) A glassy carbon electrode modified with a film composed of cobalt oxide nanoparticles and graphene for electrochemical sensing of H2O2. Microchim Acta 181: 631–638. doi: 10.1007/s00604-014-1164-2

|

|

[183]

|

Zheng L, Ye D, Xiong L, et al. (2013) Preparation of cobalt-tetraphenylporphyrin/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite and its application on hydrogen peroxide biosensor. Anal Chim Acta 768: 69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.01.019

|

|

[184]

|

Hosu IS, Wang Q, Vasilescu A, et al. (2015) Cobalt phthalocyanine tetracarboxylic acid modified reduced graphene oxide: a sensitive matrix for the electrocatalytic detection of peroxynitrite and hydrogen peroxide. RSC Adv 5: 1474–1484. doi: 10.1039/C4RA09781E

|

|

[185]

|

Kubendhiran S, Thirumalraj B, Chen SM, et al. (2018) Electrochemical co-preparation of cobalt sulfide/reduced graphene oxide composite for electrocatalytic activity and determination of H2O2 in biological samples. J Colloid Interf Sci 509: 153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.08.087

|

|

[186]

|

Liu X, Zhu H, Yang X (2011) An amperometric hydrogen peroxide chemical sensor based on graphene-Fe3O4 multilayer films modified ITO electrode. Talanta 87: 243–248. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2011.10.004

|

|

[187]

|

Yang X, Wang L, Zhou G, et al. (2015) Electrochemical detection of H2O2 based on Fe3O4 nanoparticles with graphene oxide and polyamidoamine dendrimer. J Clust Sci 26: 789–798. doi: 10.1007/s10876-014-0746-9

|

|

[188]

|

Karimi MA, Banifatemeh F, Hatefi-Mehrjardi A, et al. (2015) A novel rapid synthesis of Fe2O3/graphene nanocomposite using ferrate(VI) and its application as a new kind of nanocomposite modified electrode as electrochemical sensor. Mater Res Bull 70: 856–864. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2015.06.010

|

|

[189]

|

Fang H, Pan Y, Shan W, et al. (2014) Enhanced nonenzymatic sensing of hydrogen peroxide released from living cells based on Fe3O4/self-reduced graphene nanocomposites. Anal Methods 6: 6073–6081. doi: 10.1039/C4AY00549J

|

|

[190]

|

Xiong L, Zheng L, Xu J, et al. (2014) A Non-Enzyme Hydrogen Peroxide Biosensor Based on Fe3O4/RGO Nanocomposite Material. ECS Electrochem Lett 3: B26. doi: 10.1149/2.0041412eel

|

|

[191]

|

Zhu S, Guo J, Dong J, et al. (2013) Sonochemical fabrication of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on reduced graphene oxide for biosensors. Ultrason Sonochem 20: 872–880. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.12.001

|

|

[192]

|

Ye Y, Kong T, Yu X, et al. (2012) Enhanced nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensing with reduced graphene oxide/ferroferric oxide nanocomposites. Talanta 89: 417–421. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2011.12.054

|

|

[193]

|

Yang YQ, Xie HL, Tang J, et al. (2015) Design and preparation of a non-enzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor based on a novel rigid chain liquid crystalline polymer/reduced graphene oxide composite. RSC Adv 5: 63662–63668. doi: 10.1039/C5RA10540D

|

|

[194]

|

Zhu M, Li N, Ye J (2012) Sensitive and selective sensing of hydrogen peroxide with irontetrasulfophthalocyanine-graphene-nafion modified screenprinted electrode. Electroanalysis 24: 1212–1219. doi: 10.1002/elan.201200039

|

|

[195]

|

Jiang BB, Wei XW, Wu FH, et al. (2014) A non-enzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor based on a glassy carbon electrode modified with cuprous oxide and nitrogen-doped graphene in a nafion matrix. Microchim Acta 181: 1463–1470. doi: 10.1007/s00604-014-1232-7

|

|

[196]

|

Xu F, Deng M, Li G, et al. (2013) Electrochemical behavior of cuprous oxide–reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites and their application in nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensing. Electrochim Acta 88: 59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.10.070

|

|

[197]

|

Yang J, Zhao F, Zeng B (2015) One-step synthesis of a copper-based metal–organic framework–graphene nanocomposite with enhanced electrocatalytic activity. RSC Adv 5: 22060–22065. doi: 10.1039/C4RA16950F

|

|

[198]

|

Bai J, Jiang X (2013) A facile one-pot synthesis of copper sulfide-decorated reduced graphene oxide composites for enhanced detecting of H2O2 in biological environments. Anal Chem 85: 8095–8101. doi: 10.1021/ac400659u

|

|

[199]

|

Liu M, Liu R, Chen W (2013) Graphene wrapped Cu2O nanocubes: non-enzymatic electrochemical sensors for the detection of glucose and hydrogen peroxide with enhanced stability. Biosens Bioelectron 45: 206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.02.010

|

|

[200]

|

Liu J, Yang C, Shang Y, et al. (2018) Preparation of a nanocomposite material consisting of cuprous oxide, polyaniline and reduced graphene oxide, and its application to the electrochemical determination of hydrogen peroxide. Microchim Acta 185: 172. doi: 10.1007/s00604-018-2717-6

|

|

[201]

|

Kumar JS, Murmu NC, Samanta P, et al. (2018) Novel synthesis of a Cu2O–graphene nanoplatelet composite through a two-step electrodeposition method for selective detection of hydrogen peroxide. New J Chem 42: 3574–3581. doi: 10.1039/C7NJ04510G

|

|

[202]

|

Ding J, Sun W, Wei G, et al. (2015) Cuprous oxide microspheres on graphene nanosheets: an enhanced material for nonenzymatic electrochemical detection of H2O2 and glucose. RSC Adv 5: 35338–35345. doi: 10.1039/C5RA04164C

|

|

[203]

|

Zhu L, Guo X, Liu Y, et al. (2018) High-performance Cu nanoparticles/three-dimensional graphene/Ni foam hybrid for catalytic and sensing applications. Nanotechnology 129: 145703.

|

|

[204]

|

Li L, Du Z, Liu S, et al. (2010) A novel nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor based on MnO2/graphene oxide nanocomposite. Talanta 82: 1637–1641. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2010.07.020

|

|

[205]

|

Pan Y, Hou Z, Yi W, et al. (2015) Hierarchical hybrid film of MnO2 nanoparticles/multi-walled fullerene nanotubes–graphene for highly selective sensing of hydrogen peroxide. Talanta 141: 86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.03.059

|

|

[206]

|

Pan Y, Yi W, Hou Z, et al. (2015) Green and large-scale one-pot synthesis of small-sized graphene-bridged manganese dioxide nanowire network as new electrode material for electrochemical sensing. J Sol-Gel Sci Techn 76: 341–348. doi: 10.1007/s10971-015-3782-5

|

|

[207]

|

Dong S, Xi J, Wu Y, et al. (2015) High loading MnO2 nanowires on graphene paper: Facile electrochemical synthesis and use as flexible electrode for tracking hydrogen peroxide secretion in live cells. Anal Chim Acta 853: 200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2014.08.004

|

|

[208]

|

Feng X, Zhang Y, Song J, et al. (2015) MnO2/graphene nanocomposites for nonenzymatic electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide. Electroanalysis 27: 353–359. doi: 10.1002/elan.201400481

|

|

[209]

|

Mahmoudian MR, Alias Y, Basirun WJ, et al. (2014) Facile preparation of MnO2 nanotubes/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite for electrochemical sensing of hydrogen peroxide. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 201: 526–534. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.05.030

|

|

[210]

|

Li L, Du Z, Liu S, et al. (2010) A novel nonenzymatic hydrogen peroxide sensor based on MnO2/graphene oxide nanocomposite. Talanta 82: 1637–1641. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2010.07.020

|

DownLoad:

DownLoad: